1. CONTENTS

2. SUMMARY

3. INTRODUCTION

3.1 BACKGROUND

3.2 PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE OF REPORT

3.3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

4. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

5. OBSERVATIONS RELEVANT TO BRITISH DIVERS

5.1 DIVING IN COMPARISON TO UK

5.2 NORWEGIAN DIVE ORGANISATION

5.3 EXPEDITIONS IN NORWAY

6. WHAT’S NEXT?

7. EXPEDITION DETAILS

7.1 EXPEDITION MEMBERS

7.2 ITINERARY

7.3 DIVE SITES

7.4 DIVING TECHNIQUES

7.5 NAVIGATION AND BOATHANDLING

7.5.1 Charts and Publications

7.5.2 Passage Planning

7.5.3 Watch Keeping & Boathandling

7.6 FOOD

7.7 WEATHER

7.8 VIDEO & PHOTOGRAPHY

8. APPENDIX A – DIARY OF EVENTS

9. APPENDIX B – EXPEDITION PUBLICITY

10. APPENDIX C – ARCTIC BLUENOSE CEREMONY

The Arctic Norway Expedition was a self-funded, self contained liveaboard diving expedition from the UK to Arctic Norway. It ran for 3 weeks from 24th July to 14th August 1996, spending 15 days in Norwegian coastal waters.

The expedition involved 15 people, all BSAC members, representing six different BSAC branches. The expedition leader was Richard Scarsbrook of Trafford branch. The boat used was Maisie Graham, a 54 foot converted MFV based in Scarborough, owned and skippered by Gordon Wadsworth. A subset of the expedition team sailed Maisie Graham from Scarborough to Bergen and back. The other members joined and left the expedition in Bergen.

All the main objectives of the expedition were achieved. All 14 divers dived inside the Arctic Circle, despite a mechanical problem which left the boat immobilised in harbour at Rørvik for 6 days. What could have been a fatal blow to morale was quickly overcome by positive attitude, and the journey to the Arctic was completed by hired car and minibus. During the enforced stop expedition members undertook local shore dives; dived with a Norwegian dive centre; went to the Svartisen glacier; and made a flying visit to Sweden.

The 123 metre long wreck Konsul Karl Vesser at Ålesund, the best of the sites discovered on Maisie Graham’s 1995 expedition, was dived three times. In addition 14 new sites, including 4 wrecks, were dived and documented. A total of 174 dives were made during the expedition.

Members of the expedition covered 1800 nautical miles aboard Maisie Graham, and a further 1000 miles by road in Norway. We sailed 54 hours at night, with all members of the team taking turns on watch. The boat reached 64º52´N, 635 nautical miles north of her home port, and 130 miles north of her previous record.

About 4 hours of video footage was shot, a quarter of it underwater. Over a hundred slides, and several hundred prints were taken. This material is currently being collated, assessed and edited. The intention is to create a presentation lasting about half an hour, including a 10-15 minute video with sound commentary.

This was a very successful expedition, fortunate with mature, good natured and skilful people who

pulled their weight, and with good weather. The level of adventure was exceptionally high, with new challenges every day, for everybody. All of the team learned a lot about navigation and seamanship – and some would say they became accomplished at marine engineering. The crack was first rate. An informal survey on the way back to Bergen revealed that the highlights for most were the Arctic experience, the wrecks, and the big wall at Verpeneset. Unsolicited comments afterwards include “two of the best weeks of my life”, and “when are we going again?”.

I have been seeking out adventurous places since I started diving in 1982 and Arctic Norway has

always been high on my list of desirable places to dive. I had read accounts of the BSAC Norway

Expedition led by Gordon Ridley in 1982, which had reached Nordkapp. It had lasted 24 days and

involved driving 4200 miles.. Unfortunately, this type of expedition needs people with lots of time

to spare. In my experience two weeks is the limit for most people. I knew I could not recruit enough people with time and cash to spare for a similar venture. There had been further land based BSAC Expeditions to Norway in the following years, but they had not reached the Arctic. A land based expedition was not the answer.

Of course, one could go and dive with a Norwegian dive centre up there, but for me adventure involves being as self-contained as possible. Being taken diving does not count.

Going by boat seemed the only alternative. But where to find one? I was not keen on chartering a

Norwegian boat, even supposing I could find one. The potential for problems due to language and

cultural differences with an unknown skipper was too much of a risk. The British ketch Sula Sgeir had been used as a platform for BSAC Expeditions to Norway in the early nineties (Steve Maloney, one of our 1996 team, had been on one). However, it was no longer taking dive charters.

I had known Gordon Wadsworth, owner/skipper of the Scarborough boat Maisie Graham for a decade when at DOC93 he invited me to bring a party of divers on his planned wreck diving expedition to North East Scotland the following summer. This I did, and during a successful and high yielding trip, Gordon and I discovered a mutual ambition to dive the Arctic. It would take 3 weeks to get from Scarborough to the Arctic and back, but only 2 weeks from Bergen. We could use a skeleton crew – who need not be divers, perhaps sailors needing sea miles for their RYA tickets – to do the North Sea crossing. The main party could travel to and from Bergen by ferry or plane. The Arctic Norway Expedition Summer 1996 was born.

In June 1995 Gordon took Maisie Graham to Norway for two weeks. By the end of October we had fixed the dates and created the project plan (Appendix D). In November we began recruiting (see

Appendix B). The last of the 14 places was filled on Boxing Day, and all deposits were in the Bank by the end of February. Preparations continued steadily until departure day on 24th July. The body of this report takes up the story from there.

3.2 Purpose and Structure of Report

This report has been constructed with four separate purposes in mind:

- A memento of the expedition.

- A record of facts and impressions which can be used by expedition members as the basis for writing articles and producing presentations for publication.

- Factual information and advice for divers who wish to visit Norway and/or mount similar expeditions.

- As a submission for the BSAC Expeditions Trophy.

The Summary, Section 2, is for those wishing only an appreciation of the expedition.

Advice and guidance for people contemplating (or advising those contemplating) diving in Norway is conained in Section 5, Observations and in Section 6.

Specific factual details of our expedition, including notes on the routes followed, on each dive site visited, and on techniques employed on each aspect (diving, navigation, food, etc) are contained in the main body of the report, Section 7.

The Appendices contain supporting details referenced from elsewhere in the text, and also a Diary of Events (Appendix A). The latter contains my personal observations and notes on events, mostly

recorded soon after they occurred.

I should like to record my thanks to the following people and organisations.

- Nils Hovland of Florø, who gave us almost 50 charts.

- Bob Jones of MV Gaelic Rose, who lent us charts

- John Sawyer of Diving & Marine Services who arranged insurance

- Nora Ulyatt, who was on standby as coordinator for emergencies

- All the Norwegians we met, for their hospitality

- The British Sub Aqua Club. Expeditions like this need experienced, adventurous, self-reliant divers who share common standards and expectations. BSAC branches maintain a pool of such people, and the BSAC provides a network to access it. Without BSAC, expeditions like this would be hard to get off the ground.

The principal aim was to mount a self-contained self-funded diving expedition to reach inside the Arctic Circle.

Our objectives were to:

- Dive inside the Arctic Circle

- Revisit the best sites from Maisie Graham’s 1995 trip.

- Locate and explore new scenic and wreck sites

- Make a video of the expedition.

5. Observations Relevant to British Divers

5.1 Diving in comparison to UK

- Wrecks typical of those on the East Coast & English Channel type – ie lost by enemy action whilst on passage – tend to be in extremely deep water

- Wrecks lost by enemy action whilst at anchor wrecks – cf Dakotian, Breda – tend to be

extremely well preserved due to their sheltered location. - Wrecks from lost from foundering are the usual mix of intact and broken. There are lots of

opportunities for inshore navigation errors in Norway! - Big big walls

- Less encrusting life but noticeably different species, especially in the Arctic

- Much better vis (except in surface halocline)- more than one Norwegian spoke of 60m in February

- Many fish, including big ones, and species not seen in the UK

- Lady divers are rare in Norway

5.2 Norwegian dive organisation

- Largely through dive schools/shops, who take people out – a mixture of Norwegians, Swedes,

Germans, Dutch etc - 70 or so schools, but we were told that majority are rudimentary.

- The schools we saw had smallish, openish hardboats, £20 per dive.

- We saw 1 liveaboard advert , based in Trondheim – offering trips to Scapa Flow!

- Population is only 4 million, and distances are large – so not much club exploration has been done outside main centres of population – but there are small clubs in most areas

- Schools typically have only enough sites to keep clients happy for a week or so

- We met schools who knew of other wrecks, but hadn’t found them yet, and didn’t have time to look.

- ‘No looting’ seems to be a generally accepted rule. Perhaps as a result, the Norwegians we met were free with details of wreck sites. However this year a diver died trying to remove a bell at 85 meters near Bergen. The Norwegian Navy lifted it later to remove temptation.

- Loads of opportunities for exploring British divers. – You really need a liveaboard to give

independence and cover the distances. Try taking out school owners/divers. - According to regulations you are supposed to have a Norwegian on board. We weren’t challenged.

- The Norwegians use local information/history to locate uncharted wrecks- there are no central files. The research we did using UK documentation (Lloyds War Losses, DODAS, Warship Losses of WW2, etc) was almost useless – eg the position of Blaafjeld I stated as ‘at Namsos’ turned out to be 40 miles away. In contrast Rørvik Yacht Club had a chart on the wall with 12 local wrecks pinpointed – found on last day there.

- North of Sognefjord, some (but not all) of the inshore passages are intricate, and the offshore

sections are encumbered by unmarked/unlit rocks. A high level of navigation and pilotage skills is needed, especially for night sailing. - The good weather and long hours of daylight helped a lot. We managed to get by with less sleep, and to cope with interrupted sleep patterns. Long daylight hours also mean fewer night sailing hours.

- GPS errors are significant, longitude errors exceed 100m even using new Norwegian charts. Be careful about differences between WGS-84 and Norwegian chart datum.

- Costs are generally higher than the UK. Groceries maybe +50%, petrol £4 per gallon, red diesel 26p per litre, a weeks hire of a 10-seater minibus and a Mondeo was £900, a round of 4 pints doesn’t leave much change from £20. Overnight self-catering accommodation is cheap though – basic bunkhouse (hytt) with decent showers £3.50 a head, smart house with all mod cons £7.50 a head.

- You must have decent charts for an expedition like this – you don’t have time to feel your way through. Norwegian 1:50,000 charts are best, but you need lots of them at £14 each. Norwegian small scale charts are only useful for passage planning.

- A good crew is invaluable when things don’t go to plan – both for skills they have (engineering etc) and for flexibility, cheerfulness etc.

- Norway has many attractions per se – people, scenery, wilderness, history, etc. Extended visits ashore are very worthwhile. Plan them into your expedition. If you like Scotland you’ll love Norway.

- One of the expedition objectives was to make a video/slide presentation of the expedition. Work on this has started, with target completion at the end of October.

- Most of the expedition members are certain to return to Norway, both to dive and to see the scenery, individually or in groups.

- Gordon has outline plans for an extended Maisie Graham visit in 1997, which could enable several groups to experience Norwegian diving (tel 01723 362085).

- A liveaboard expedition to the White Sea around Murmansk is being organised for 1997 by Norwegian Ole Rønning (tel 47 784 17228; Email oronning@oslonett.no).

The Summer 1996 expedition began with an ambition to dive in Arctic Norway which had been on my personal “must do list” for several years. The experience of going on this expedition has now added the ollowing entries to the list, to be implemented when time and money permit:

- A short February trip – 60m vis, use a local dive centre for a few dives, live ashore where it’s warm, experience life in the snow.

- More adventure – 1st British liveaboard diving expedition to North Cape and Spitzbergen. Go to 80ºN. 420 nm offshore passage from Torsvåg to Spitzbergen – same as Scarborough to Bergen, but more icebergs and polar bears.

- Trips to explore smaller areas in more detail at fewer miles per dive. Three areas particularly appeal:

- Deep fjords – egs Lysefjord near Stavanger; Hardangerfjord south and Sognefjord north of Bergen; Nordfjord north of Florø; or the Tromsø area.

- Narvik and Lofoten – the ultimate wreck/scenic combination, less than 100 miles apart? A 2 week trip to make the most of it.

- Wrecks and walls exploratory diving in the Kristiansund/Ålesund area

All the expedition members are experienced and active BSAC members, representing six different branches. The average age of the group is over 40. The youngest member is in his late 20s, and the eldest is already a Senior Citizen. All the team members are affable and positive people, which made for a notably good humoured expedition. Furthermore every individual had unique skills and knowledge which were needed, were freely given, and which added to the success and enjoyment of the holiday.

Skills used included the technical, obviously – cooking, engineering, navigation, boathandling, dive marshalling, etc – and also the artistic – story telling, comedy, and even poetry. Amongst the more unusual skills that were available when needed were knowledge of import/export procedures, off-road driving on building sites, and professional expertise with international credit card systems.

| Name | BSAC Branch | Qualification | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigel Thomas | Ashbourne | 1116 | Dive Leader |

| Roz Amos | British Timken | 73 | Dive Leader |

| Jeff Kay | Darwen | 47 | Advanced Diver/Open Water Instructor |

| Pat Kay | Darwen | 47 | Dive Leader |

| Steve Maloney | Darwen | 47 | Advanced Diver/PADI OWSI |

| John Wright | Darwen | 47 | Advanced Diver |

| Shirley Higson | Horwich | 435 | Dive Leader |

| Richard Sackville-Bryant | Horwich | 435 | Advanced Diver/Open Water Instructor |

| Don Tovey | Scarborough | 83 | Scarborough to Bergen only |

| Gordon Wadsworth | Scarborough | 83 | Owner-Skipper RYA/DTp Yachtmaster Advanced Diver |

| Steve Boothby | Trafford | 584 | Advanced Diver |

| Anne Scarsbrook | Trafford | 584 | Advanced Diver/Club Instructor |

| Jen Scarsbrook | Trafford | 584 | Advanced Diver/Advanced Instructor |

| Richard Scarsbrook | Trafford | 584 | Expedition Leader RYA/DTp Coastal Skipper First Class Diver/Advanced Instructor |

| John Ulyatt | Trafford | 584 | Advanced Diver/Club Instructor |

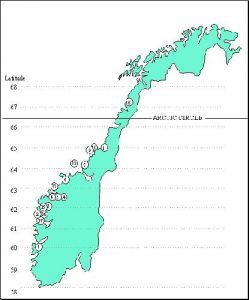

The map below shows the main route followed by the expedition. Maisie Graham covered 1800

nautical miles on her voyage. The passages between ports of call are shown in Table 1 (distances in nautical miles). The North Sea crossing was direct from Scarborough to just north of Stavanger on the outward leg, and direct from Bergen to Scarborough on the return. In Norway the majority of passages used the skjærgård, waters sheltered from the Atlantic by outlying islands. This provided calm water, sheltered diving and excellent scenery at the expense of sometimes intricate navigation. Outside passages were enforced where there are gaps in the skjærgård between Haugesund and the entrance to Bomlafjorden (59°30´N); around Stattlandet (62°10´N); at Hustadvika (62°50´N); and at Folla, south of Rørvik (64°30´N). Fortunately all these passages were in calm weather except the northbound passage of Hustadvika where the seas were moderate. In calm weather we elected to take additional outside passages to simplify navigation on the final night passage to Rørvik, and for speed on the way back south.

Maisie Graham’s northbound voyage was terminated prematurely at Rørvik (64º54´N) in the early hours of 1st August by a mechanical problem. It turned out to be a badly worn gearbox bearing.

Fortunately the skipper had spotted the problem before it caused a breakdown at sea. The boat was delayed for 6 days while spare parts were sent from the UK. The actual dismantling and reassembly took engineers Gordon, Steve Boothby and John Wright about 12 hours in total. After repairs and adjustment no further problems were encountered, and the southbound boat journey began early on 7th August.

| Date | Time | Lat | Long | Passage | Total | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25/7 | 0230 | 54°17´N | 0°24´E | – | 0 | Left Scarborough with 6 souls on board |

| 27/7 | 0800 | 59°25´N | 5°17´E | 370 | 370 | Stopped at Haugesund for fuel & provisions |

| 27/7 | 1200 | “ | “ | – | 370 | Left Haugesund |

| 27/7 | 2300 | 60°23´N | 5°20´E | 70 | 440 | Tied up alongside Bergen |

| 28/7 | 1700 | “ | “ | – | 440 | Embarked 9, disembarked 1, sailed from Bergen |

| 29/7 | 0430 | 61°36´N | 5°02´E | 80 | 520 | Arrived Florø to purchase further charts |

| 29/7 | 0900 | “ | “ | – | 520 | Departed Florø |

| 30/7 | 0200 | 62°28´N | 6°09´E | 100 | 620 | Arrived Ålesund, to dive local wreck & purchase additional charts |

| 30/7 | 1530 | “ | “ | – | 620 | Sailed from Ålesund after diving |

| 1/8 | 0600 | 64°52´N | 11°14´E | 250 | 870 | Put into Rørvik to investigate gearbox problem |

| 7/8 | 0200 | “ | “ | – | 870 | Sailed from Rørvik after repairing gearbox with new bearings |

| 7/8 | 0600 | 64°36´N | 10°57´E | 25 | 895 | Put into Utvorden for realignment of engine/gearbox |

| 7/8 | 1000 | “ | “ | – | 870 | Sailed from Utvorden |

| 8/8 | 2100 | 62°28´N | 6°09´E | 225 | 1120 | Arrived Ålesund after diving local wreck |

| 9/8 | 0430 | “ | “ | – | 1120 | Left Ålesund |

| 9/8 | 2200 | 61°36´N | 5°02´E | 100 | 1220 | Arrived Florø |

| 10/8 | 1130 | “ | “ | – | 1220 | Left Florø after diving local wreck |

| 10/8 | 2300 | 60°23´N | 5°20´E | 80 | 1300 | Arrived Bergen |

| 11/8 | 1430 | “ | “ | – | 1300 | Disembarked 10, sailed from Bergen |

| 14/8 | 0230 | 54°17´N | 0°24´E | 420 | 1720 | Arrived Scarborough |

Travel from Rørvik to the Arctic was by road on Saturday 3rd August, using hired self drive vehicles. It took a full day to travel 600km from Rørvik across the Arctic Circle to Rokland, including a short detour into Sweden at Junkerdal. We stayed overnight in bunkhouses. The following day we travelled a further 30km north through Rognan and Bodn to the shore of Saltfjorden for a dive. One vehicle (6 people in a Ford Mondeo) returned to Rørvik that day. The other 8 members, in a Ford Transit, made an overnight stop in a self catering lodge just north of Mo-i-Rana. After a 60km detour to visit the Svartisen glacier the second vehicle arrived back at Rørvik on Monday evening.

Other necessary road journeys were 250km to Grong and back to collect the Ford Transit, because no minibuses were available in Rørvik; 600km to Trondheim and back to collect the new bearings for the boat from the airport; and 80km to the launch site for dive 11.

In all we travelled well over 1000 miles by road in Norway. Most drivers stay close to the general

speed limit of 90kph. Although the roads are fairly empty, there are relatively few safe

overtaking opportunities for those who wish to go faster.

The following map shows the locations of the 15 dive sites we visited. The table on the succeeding

pages shows for each dive site:

- Ref – the corresponding number on the map

- Date & Time – the date and approximate time of the dives

- Place – the nearest place name to the dive location

- Lat & Long

- Dives – the number of person-dives carried out

- Max Depth – the maximum depth that any of the divers reached on the site

- Description – details of the site observed at the time, or in the case of wrecks researched later

| Map ref | Date | Time | Place | Lat | Long | Dives | Max depth meters |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27/7 | 1800 | Huftarøy | 60°04´N | 5°18´E | 6 | 20 | Cliff to 20m then sandy shelf. Scallops and Angler fish | |

| 2 | 29/7 | 1230 | Skavingen | 61°44´N | 4°57´E | 12 | 36 | Island sloping at 20° to NW. Broken shell bottom. Scallops and angler fish. Many nudibranchs. | |

| 3 | 29/7 | 2000 | Ringlaura Rock, Voksa | 62°13´N | 5°27´E | 11 | 36 | Pinnacle with sides descending in small steps. Good fish life | |

| 4 | 30/7 | 1000 | Ålesund | 62°30´N | 6°07´E | 12 | 37 | Wreck of Konsul Karl Vesser. 123m in length. Upright and substantially intact. Easy access to engine room. Extensive video footage shot. | |

| 5 | 30/7 | 1500 | Ålesund | 62°30´N | 6°07´E | 8 | 40 | As dive 4 | |

| 6 | 31/7 | 0930 | Røstøya | 63°27´N | 8°53´E | 11 | 30 | Bedrock outcrops 15m high at 60° angle, and coarse sand slope to depths. 30m vis – Mediterranean feel to this site, but more fish. | |

| 7 | 31/7 | 2030 | Skojorafjorden | 64°06´N | 10°08´E | 11 | 42 | Vertical and overhanging wall to 85m | |

| 8 | 4/8 | 1030 | Skjerstadtafjorden | 67°03´N | 15°27´E | 14 | 46 | **ARCTIC DIVE** Boulders from man-made mole to 10m, then sand slope to 20m, then steep bedrock rolling down into darkness. Atmospheric. Life noticeably different to that seen further south – unusual hydrozoa, crustaceans, and starfish. The surface layer of fresh water was about 5m thick and moving at about half a knot. The salt water layer below was stationary. | |

| 9 | 5/8 | 1400 | Rørvik harbour | 64°52´N | 11°14´E | 2 | 14 | Boulders on gravel. Usual harbour rubbish plus flatfish | |

| 10 | 5/8 | 1500 | Nærøysundet | 64°50´N | 11°16´E | 4 | 15 | Sand and gravel plateau on W side of channel. Slack water at local HW/LW. Abundant flatfish | |

| 11 | 6/8 | 1500 | Urshalsvaagen | 64°53´N | 11°43´E | 12 | 35 | Wreck of Blaafjeld I scuttled by locals after German air attack sank nearby ship Sekstant in May 1940 and stray bombs fell on village. She is a 1146 tonne Norwegian steamship, 226 feet long. An exceptionally intact wreck, with masts and funnel still standing. | |

| 12 | 7/8 | 1600 | Kaura LH | 64°14´N | 10°08´E | 14 | 46 | Kaura lighthouse stands on an island out in the ocean. There is a 20° bedrock slope, with occasional 5m steps, down to depths of 500m. Interesting life in crevices and on kelp – which grows down to 30m. Vis above 30m was only 15m, below this it suddenly leapt up to more than 30m of deep blue water, giving a good oceanic feel to the dive | |

| 13 | 8/8 | 1030 | Bjogna | 63°03´N | 7°18´E | 14 | 29 | An isolated reef on the edge of the main shipping channel outside Kristiansund. The wreck of the Wavelet (2992 tonne British iron ore carrier wrecked 27/8/1916 on passage from Narvik to the Tees) lies on the SE side. This wreck is well broken up, but the 3 cylinder engine lying on its side, 2 boilers, and various winches were all there. The Olaf Kyvve and an unknown sailing vessel are reported to be wrecked on the same reef. | |

| 14 | 8/8 | 2000 | Ålesund | 62°30´N | 6°07´E | 14 | 44 | As dives 4 and 5 | |

| 15 | 9/8 | 1500 | Verpeneset | 61°54´N | 5°12´E | 10 | 52 | A magnificent wall plunging from 20m to 160m in 30m+ vis. The top 8m was fresh water and the vis was poor. Below this was a sand and boulder slope leading to the wall. Angler fish were caught here. Life on the wall appeared sparse except for some large specimens of Bolocera. However this is a dive for enjoying the situation rather than examining the wildlife in close detail. | |

| 16 | 9/8 | 2000 | Midtgulen | 61°44´N | 5°12´E | 9 | 45 | The wreck of the Helga Ferdinand, a 2566 tonne German steamship bombed by the RAF in November 1944. This wreck is upright and is very intact. We shot some video footage on this dive. Another wreck charted nearby is believed to be the Aquila, a 3495 tonne German steamship sunk in the same attack. We were told that it lies on its side. | |

| 17 | 10/8 | 1000 | Florø | 61°37´N | 5°04´E | 11 | 30 | This was an unknown wreck which shows at the E end of Florø harbour. Not much remains beyond what is visible above the water. The wreck is surrounded by debris of moderate interest to keen rummagers. |

Normal BSAC diving practices were followed throughout the expedition. Compressed air was the only breathing gas used. All divers carried one or more AAS each.

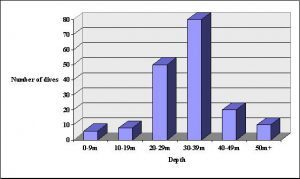

The depth of the dives undertaken is shown in Figure 3. Partly because of the depth and the age of the divers, but principally because it is what the divers on this expedition always do, a cautious approach was taken to decompression. Decompression stops were conducted using a vertical datum. In the case of wreck dives the datum was a shot line or waster, and in the case of scenic dives it was the seabed or cliff face. Each diver used a dive computer, usually performing several minutes of safety stops after the computer had cleared.

There was a noticeable tidal flow at site 6, and SMBs or delayed SMBs were used. The other scenic sites were free of currents and there were no waves so it was easy to spot the divers when they surfaced. However, sites 2 and 12 were relatively exposed, and some buddy pairs chose to use SMBs. The boat was kept mobile at the scenic sites, and divers were picked up where they surfaced.

On wreck sites the waster method was used to moor the boat over the site, except at site 11 where a buoyed wreck was dived from a Norwegian boat and the buoy line was used for descent and ascent. The waster method involves locating the wreck on the echo sounder and anchoring into it with a grapnel. The first pair of divers descend the anchor line carrying a line with a weak link at the end. If the wreck is already buoyed (dive 16) the anchor is not used and the divers descend the buoy line carrying the waster. The weak link is tied into a solid piece of wreckage close to the arrival point on the wreck. The line is tended at the surface, and after a prearranged signal from the divers, or after a prearranged amount of time has elapsed, the line is tightened and made fast at the surface. The second pair of divers clear the anchor from the wreck, and it is then retrieved. When all diving is completed, the waster is pulled from the wreck either by winch or by the boat itself (going astern to avoid fouling the propeller).

Optionally, divers can take additional wasters with them and tie them off by a prearranged time towards the end of their dive. Multiple wasters avoid the need to return to the entry line, and provide subsequent divers with access to extra known features on the wreck, which helps to build up a coherent picture of the wreck. Multiple wasters were used on Konsul Karl Vesser (dives 4, 5 & 14).

The visibility, light, and absence of silt was so good on all the sites dived that underwater navigation was easy. No special methods were needed even for penetration of the engine room of Konsul Karl Vesser (see video).

7.5 Navigation and Boathandling

At the start of the expedition we were equipped with a selection of British and German charts covering the whole of our intended cruising area. South of Sognefjord (61º00´N) we had adequate large scale charts. North of this, the coverage was mainly at 1:300,000, with only a few larger scale charts around Ålesund and Smøla. Overcast weather at the start of the expedition meant that we were experiencing longer hours of darkness than expected and it quickly became obvious that we would not be able to navigate safely inshore at night without additional large scale charts. But if we did not sail at night, we would not make fast enough progress to meet out objective. We purchased about a dozen Norwegian 1:50,000 charts, and were fortunate to meet Nils Hovland in Florø, who gave us nearly 50 more older charts at the same scale. The donated charts extend far beyond Narvik, paving the way for further adventures in the future.

The Norwegian 1:50,000 charts are excellent However, some of the symbols and abbreviations are distinctly different to those found on British charts. This was particularly, but not exclusively, true of the older charts where some of the abbreviations for light characteristics were hard to understand. There is an ancient system of navigation peculiar to Norway, based upon stone towers painted black, often with a white stripe, called Vardes. These and other unusual marks, all common and very relevant to safe navigation, have special chart symbols – but only on Norwegian charts. We purchased a copy of the Norwegian equivalent of 5011, and found it useful.

The Norwegian small scale charts at 1:300,000 appear to be designed for passage planning, and I found them relatively unhelpful. Small scale Admiralty charts of Norway contain more detail and are adequate for navigation by day – in good weather – in the wide channels followed by the Hurtigruten ships, such as the passage from Straumen to Trondheim.

Each Norwegian 1:50,000 chart has an index chart printed on the back. At a pinch this would do for passage planning. We used the German 1:300,00 charts.

We had a copy of the 1996 edition of Norwegian Cruising Guide by Armitage & Brackenbury. It covers the entire Norwegian coast. We found it very useful for identifying towns and villages where we could obtain diesel, water, supplies, shelter, etc if required. It also contains useful background information. We also had one volume of the 5 volume Norwegian pilot, Den Norske Los. In addition to the information in Norwegian Cruising Guide it gives comprehensive passage information, which can only be used with the relevant charts. We found that having the charts rendered it largely superfluous.

The following information sources also proved useful:

- A nautical almanac (ours was Reeds European 1993 edition). The section on Radio & Weather Services was helpful. In Norway almost all VHF communication takes place via coastal radio stations on working channels. There is no equivalent of HM Coastguard to talk to. Unlike the UK where a coastal radio station has one or two working channels, in Norway it may have a dozen. Which one you can receive depends on where you are. Even when they announce on Channel 16, they don’t tell you what the working channels are. The almanac has a list of transmitters, their lat & long, and their working channel – so you can work out which one to listen on.

- A list of tidal constants for various ports, and a tidal curve. We applied these to the Liverpool tide table, with adequate results. For example, we were able to calculate correctly that at Bergen the tide would not lift Maisie Graham into the scaffolding under which she was moored!

- A copy of the Dykkeguide ‘96 published by the Norwegian diving magazine Dykking. It contains

contact details for all the dive centres and dive clubs in Norway.

- On the Internet, the website at http://www.sol.no/sportweb/scuba/dive_eng.htm contains similar information to that in Dykkeguide ‘96 plus links to further information on diving in Norway including Norwegian diving regulations.

- A tourist guide to Norway. We used the Insight Guide.

- A road map was useful for orientation (it later became essential for driving). We had the AA Road Map of Scandinavia, and a Michelin map. Drawing and annotating the progress of the expedition on one of these maps, as events unfolded, proved a very effective method of record keeping.

I did most of the passage planning in Norway, and found the following approach successful.

- Determine the most suitable route to fit in with the overall plan (get to the Arctic/get back to Bergen in time for the ferry). This entails striking a balance between the shelter, comfort, proximity to dive sites, scenery and places of interest, and navigational interest of inshore routes against the navigational simplicity and directness of offshore passages. The main influences are the weather (calm/windy/misty) and the state of the crew (tired/rested, green/learning, seasick/well, etc).

- Draw the route to be followed over the next 24 hours or so onto a small scale chart.

- Take out the corresponding large scale charts and draw the required route on them, making sure the transition from one chart to the next is clear.

- Mark the approximate expected position at hourly intervals, assuming average speed which in our case was 7 knots.

- Allow for 2 dives at 2 hours each per day (unused time to be used for wreck searches, time ashore etc)

- Correct the expected positions from 1800 onwards to allow for all 4 hours having been used by 2200, when night watches will commence. Expected positions before 2200 are not adjusted on the chart – arrival time is as calculated plus time used out of the diving allowance.

- Work out the watch rota, putting the strongest crews on watch on the trickiest passages.

- Mark likely dive sites in daylight hours on the charts. Work out the eta. Draw up a list of potential dive sites showing lat/long, eta, and the type of site (wall/wreck etc).

- Brief each team on the plans for their watch. Point out the potential dive sites.

7.5.3 Watch Keeping & Boathandling

In Norway, we stood two hour watches in teams of three when sailing at night – a helmsman, a navigator, and a lookout. We used a formal rota system from 2200 to 0800. Outside these hours, watch teams were assigned informally. At the start of the expedition, only a few of the crew had much experience of navigation. By the end everyone had done stints, supervised when necessary, at the wheel and at the chart table, in circumstances appropriate to their skill level. As a result everybody learned a great deal. This aspect of the expedition – including the night sailing – proved very popular.

The waters we were navigating in were new to every person on board. Some of the inshore passages were intricate and pilotage required intense concentration, although usually well marked. Norwegian navigational aids differ from those in the UK. For example, a cardinal or lateral mark is typically a slim inclined pillar about a metre high. Topmarks are rare, which makes life difficult for those of us who work out the characteristics of cardinal buoyage by the topmark (wineglass equals west, cones point to black stripes, etc). The majority of lights are occulting, and sectored lights are used extensively. Because the water is so deep, there are few buoys, and it is important to remember that what you are aiming at is probably standing on a rock. The fact that some of our charts were old also caused some problems. Some light characteristics had changed (usually pillars with a yellow light had been superseded by a lateral mark), and new bridges and overhead cables had appeared. The latter are common in Norway, and it is important to be aware of your boat’s air draught. Many Norwegian charts are drawn to different datums than WGS84 which is used by Maisie Graham’s GPS to express positions in latitude and longitude. This gives rise to errors such that you may be 100 metres or more east of where you think you are.

Because of these complexities it was necessary to use as many means as possible of maintaining safe progress. As well as traditional methods such as clearance lines, we used radar, VRM, GPS, depth alarms, and forward looking sonar. In twisting narrow channels the latter was sometimes alarming when depths can rise rapidly from 200 metres to the surface.

Apart from the fish caught during the expedition, all our food was brought from the UK. Meat was vacuum packed and frozen in the UK, and transported in coolboxes. Some meat dishes were precooked in the UK, by members of the expedition, and then vacuum packed and frozen by a local butcher. We took a large quantity of fresh fruit and vegetables. We found that potatoes, carrots, onions, garlic, peppers, tomatoes, and cabbage kept well for the duration of the expedition. So did apples and oranges, eggs and cheese, and wholemeal bread. Bread mixes, pizza base mix, baking supplies such as flour and dried fruit and nuts, dried pulses, stock cubes, and a variety of herbs, spices, oils and vinegars, were all used extensively.

Food preparation, serving and washing up was organised by rota. We were fortunate to have several accomplished cooks in the party. In particular, Jen, Pat and Shirley took the lead in turning out a succession of inventive and tasty meals and snacks. The highlights included onion and walnut bread, monkfish and scallop chowder, and Shirley’s magnificent bread and butter pudding.

Each person brought their own supplies of beer, wine, and spirits from the UK. It is possible to ship duty free stores since Norway is outside the EC. However, the savings do not outweigh the hassle involved. Drinks in Norway are very expensive, although this did not stop some of our party from visiting the pub whenever the opportunity arose.

We were fortunate with the weather. An acquaintance who returned to Bergen the day we arrived, sailing his 45 foot catamaran Tinkerbelle to North Cape and back over four weeks, had experienced unrelenting cold and drizzle. It was rough for our first day out of Scarborough, and wet for the first two days in Norway, and wet again for two days at Rørvik. Apart from that, a high was settled over Scandinavia, and we enjoyed clear skies and warm sunshine, and light winds. The return crossing to Scarborough was threatened by SE gales, but they failed to materialise and the strongest winds were SE force 5 on the beam.

Water temperature was typically 14ºC. The waters of Norway’s west coast are warmed by a branch of the Gulf Stream which flows north forming the main input to the Arctic circulation.

During the trip we discovered that whereas in the UK weather forecasts are broadcast regularly on VHF, in Norway they are not. Only strong wind warnings are broadcast, on working channels (see above) only. If you want forecasts you have to register your callsign with the Coastal Radio service prior to your voyage, and then you are charged on each occasion. We got our forecasts by asking the locals what it said in the newspapers and on TV.

About 4 hours of video footage was shot, a quarter of it underwater. We had an informal list of shots required, but no formal storyboard. Three different cameras were used, one 8mm, and the others Hi8 format. Over a hundred slides, and several hundred prints were taken. This material is currently being collated, assessed and edited. The intention is to create a presentation lasting about half an hour, including a 10-15 minute video with sound commentary, supplemented by transparencies and OHP slides.

At the time of issuing this report, all the video material has been indexed, and a 30 minute rough edited chronological documentary has been prepared and is available for review. The next step is to correct editing errors; shoot and insert additional material (titles, maps, etc); prune the material down to about 20 minutes, and supplement the original soundtrack with commentary and music.

8. Appendix A – Diary of Events

This is a personal account of the expedition.

August 1994 The idea for this expedition came during a 2 week serious wreck diving expedition to NE Scotland on Maisie Graham when Gordon Wadsworth and I discovered a mutual ambition to dive in the Arctic. Autumn 1995 Gordon and I agreed the outline of the expedition. We worked out that the minimum duration was 3 weeks. We hoped to get as far as Narvik. The chance of finding enough people with 3 weeks to spare was minimal so I came up with the idea of a skeleton crew to cross the North Sea, with the others travelling by ferry. We had 5 or 6 definite members, and I agreed to produce some publicity in time for DOC95. November 1995 Despite heavy canvassing, we only got one recruit at DOC. I then circulated local branches, and the local dive shop, and placed a posting on the Scuba-UK mail list via the Internet. I created a project plan for the expedition, using Microsoft Project. December 1995 Canvassing continued through the Dinner Dance season. The last place was filled on Boxing Day. In the end 2 places were filled via John Sawyer at Diving & Marine Services, one was a contact of Gordon’s, and the rest came from my own contacts. The experiment with the Internet produced 4 enquiries, 1 of which would actually have gone, but unfortunately the trip was full by the time he had made his mind up. January 1996 Wreck research, mainly concentrated on World War II threw up a list of 93 wrecks in the area we planned to visit. Unfortunately most of the positions were vague eg “off Namsos”. I managed to borrow some Norwegian charts from Bob Jones skipper of the Gaelic Rose. February 1996 The contingent from Darwen, Horwich and Trafford branches met at Anne’s house in Bolton to discuss arrangements, view Norway 95 video, establish food likes/dislikes etc. Shirley does ferry bookings July 1996 Ferry travel & insurance finalised by Shirley. Agree stores list with Gordon. Do shopping. Pre-cook meals. Finalise contingency plans. Send out final briefing letter 20 July Some of those going by ferry deliver their gear to Gordon’s house in Scarborough. 24 July Remaining gear of those going by ferry delivered and loaded aboard. North Sea crew arrive and board. Weather windy – Tyne NW5-6, Dogger NW5-6/7. We decide to sail at first light. Go for meal in local restaurant. 25 July 0100 – Gordon arrives back aboard. He and I move the boat to the fuelling berth and take on diesel and water. Full tanks plus 2 barrels of water, 2 open tubs of water, and 1 barrel of diesel carried on deck. 0230 – In harbour, weather appears to have moderated. We decide to go for it, and sail without waking the others. Outside the harbour it is rough and confused with waves rebounding from the harbour wall as we turn NNE in the darkness.

0330 – Gordon has gone to bed and I am alone at the wheel. It is still rough, but now you can just see the big ones before they hit the port bow. We are running at reduced revs to ease the strain on boat and crew.

0900 – The weather is moderating. Two of the crew are in their bunks, badly seasick. The rest of us are up. I have been seasick, fortunately mildly, for the first time in my life. We gradually settle into a routine of cooking, eating, helming, chatting, and sleeping.

1200 – We are now up to 700 revs, normal cruising speed.

1750 – The sea is now down to slight, and the forecast is good – NW2-3 for Viking, Forties, and North Utsire, the areas on our route. The sun is shining.. We draw up a watch rota for the coming night.

26 July We pass some oil rigs about 10 miles away during the night Navigation is easy – you just follow the line on the chart plotter. The North Sea is a lonely place, and since leaving the English coast we have seen few other vessels, even on radar.

We pass only 50 miles from the Battle of Jutland wreck HMS Invincible, but resist temptation.

By 2200 we are approaching the traffic separation scheme off Stavanger, and are starting to see more ships.27 July 0400 – landfall at Kvitsøy and into sheltered waters. 0800 – stop at Haugesund to buy fuel and provisions. Raining.

1400 – The weather has brightened and we stop for a dive. Angler fish for tea.

2300 – arrive at Bergen and tie up right in the centre of this lively city. Go ashore to sample the nightlife.

28 July Still raining intermittently. Lie in, then check in with customs, who don’t seem very interested. Ferry bearing most of the others arrives at 1400, and they are aboard by 1430. Nigel arrives in the sidecar of a BMW. Discover that some bags containing a mixture of dive gear, clothes and sleeping bags have been left on deck during the crossing. Everything is wet. Find a place with tumble dryers, and dry them. 1700 – Leave Bergen for the Arctic.

2100 – Set watches, in groups of three, for the night and early morning.

29 July 0200 – Up for my watch. Previous watch is struggling. Our charts, whilst covering our intended cruising area, prove to be insufficiently detailed to identify all the lights we can see. In the darkness we have had a close encounter with a buoy. At one point we have to heave to until a ship passes and we can follow it through a particularly tricky passage. It is obvious that we shall have to buy more charts if the expedition is to get to the Arctic and back in the time available. We put in to Florø, the next sizeable town. I stay up until 0700 to make a shopping list of essential and desirable Norwegian 1:50,000 charts. 0800 – A friendly local has left fresh rolls, milk and coffee on deck for us. Later a huge man, Nils Hovland the local Traffikkinspektør, arrives and starts chatting. On learning our destination, and our problem with charts, he says he may be able to help. He drives off and returns ten minutes later with three large rolls of charts which he gives us – nearly 50 charts!

1000 – We still had to buy a few new charts in Florø. They were out of stock of 3 of them, so we will buy them in Alesund. Sail.

1230 – Stop for a dive. The scenery improves – it’s like the Outer Hebrides, but ten times the scale. At Marøy we pass right over a wreck. Unfortunately it’s 53m to the top. Later, rounding Statlandet, one of the outside passages, the sea is calm and there are many reefs and shoals. This place must be littered with wrecks although none is charted. We don’t have time to stop and explore if we are to achieve our goal of getting to the Arctic.

1600 – An ominous rattle is coming from the compressor. “Sounds like the main bearings” say the engineers, gloomily. Problem discovered with meat. Supplies for two weeks were supposed to have been vacuum packed and frozen. We discover that whilst everything has been frozen, only the pre-cooked meals have been vacuum packed. Nasty smells are beginning to come from the coolboxes.

2000 – Weather much brighter. Stop for another dive. Gordon searches for a charted wreck, but can’t find it. Compressor noise diagnosed as collapsed sealing washer. Work on making replacement started.

30 July 0130 – Arrive Ålesund. Party. Gordon keen to make 2 dives on local wreck tomorrow. I want to make one dive and press on northwards. 0700 – Awake to find Gordon working on compressor.

0830 – Compressor mended. Nigel & I go to buy last 3 charts. Others go out to dive wreck.

A mass cooking programme is started to rescue the meat. Some has to be thrown away, but we dine handsomely on roast meat for the next 3 days. Only the expedition leader and seagulls will eat the “rescued” chicken pieces.

1530 – After a second dive on the local wreck we set sail northwards, for the first of two consecutive overnight passages. If all goes to plan we will now cross the Arctic Circle around midnight on Thursday 1st August. The delays at Florø and Ålesund have meant that we shall not have time to visit Lofoten. My strategy now is to minimise further travelling, and maximise the use of remaining time for exploration. This means a quick dash to the Arctic followed by a more leisurely voyage back.

2230 – We have reached the second of the places where one must sail in the open ocean outside the sheltering islands. It is the Hudstavika, a notorious stretch of water. The chart is littered with warnings about Dangerous Waves. The navigation is tricky, and we are carefully plotting our position from the GPS to avoid charted rocks when our lookout spots a rock half a cable directly ahead. We make a rapid course adjustment.

31 July Returning to the inside passage in the small hours we pass under a bridge which the chart said was higher than it actually is. The flexibility of Maisie Graham’s MF radio aerial is severely challenged. 0300 – The less experienced sailors in the crew are now beginning to enjoy navigating and helming in the sheltered waters east of Kristiansund.

1000 – Stopped for a dive in calm water and bright sunshine. Nigel unsuccessfully tackles a giant angler fish and gets taken for a swim. Gordon has noticed some discoloration in the gearbox oil, and takes the opportunity to change the oil while we dive.

pm – the inshore navigation is intricate and demanding, but good fun. We search without success for another charted wreck.

2000 – Stop to dive an excellent vertical wall. Although the prevailing wind is onshore, it hits the high cliffs and rolls down, giving a gentle offshore breeze at the site.

I decide that the overnight passage should be out in the ocean, because inshore is too demanding at night in this area, unless Gordon and I stay up all night.

1 August 0100 – A submarine is sighted. The gearbox oil has again become discoloured, and the gearbox is getting hot. A faulty bearing is suspected. We reduce revs. 0500 – We tie up in Rørvik, the next sizeable town, in order to strip and examine the gearbox. We are alongside a large whaler, so given our predicament all Greenpeace and Save the Whale T-shirts are banned.

0900 – Bad news. One of the gearbox bearings is damaged and must be replaced. Gordon has a set of spares in Scarborough, so we will have to get these flown out. Until the boat is repaired, we are immobilised. The mood of “we won’t get to the Arctic” is rapidly replaced by “how are we going to get to the Arctic?”. By early afternoon we have:

- Arranged for the new bearings to be packed ready for collection by the courier. The courier is promising 24 hours delivery, with possible collection this afternoon.

- Investigated alternative transport arrangements for getting to the Arctic. Self-drive car hire is easily the cheapest and most flexible. We can’t get a single vehicle big enough to take all 14 of us, so I arrange an option for a 10 seater Transit and a Mondeo, to be confirmed.

- Contacted the local dive centre.

- Worked out that the latest we must leave for Bergen on Maisie Graham is Wednesday next week, which would still leave time to dive on the way back.

- Had showers ashore at the local yacht club.

- Been sunbathing.

Later in the day it begins to rain. The courier now can’t collect until Friday afternoon, for delivery Saturday or Monday, so we decide to hire the vehicles. This involves driving 130km each way to Grong to collect the Transit. The scenery is excellent. There are spectacular cliffs plunging into fjords, but they look like a boat would be needed to dive them.

We decide to mount our Arctic excursion on Saturday, and book overnight accommodation.

A busy day, but no diving.

2 August A wet day. The engineers do as much preparation as they can for rebuilding when the parts arrive. The courier picks up the bearings in Scarborough in the afternoon. They now say delivery will be Monday or Tuesday. This means that all 14 of us will go to dive in the Arctic.

Task of the day is getting water, because we are running low. Unfortunately the jetty we are on does not have a tap. We take two 50 gallon barrels in the Transit and fill them. Getting the filled barrels to the edge of the jetty is easy. While attempting to use the derrick on the whaler we manage to drop one barrel in the sea and wedge it between the whaler and the jetty. Eventually we prod it into the open with a boathook, launch the inflatable, tow the barrel alongside, and parbuckle it aboard. The second barrel has no bung, and the bung in the first barrel is a different size. We decide to wait until the tide brings the gunwhale of the whaler level with the edge of the jetty, then roll the barrel down a plank. This works after a fashion, and the barrel is still almost half full by the time we get it aboard.We pack the dive gear for the Arctic trip – 7 sets of gear, suits and all, to be shared between 14 divers because that’s all we can fit in the vehicles.1930 – Sievert, the proprietor of the local dive centre joins us for dinner. He tells us about his local dive sites. We’d already spotted most of his top scenic sites on the chart, but he tells us he has some good local wrecks, and mentions others he’s still searching for. We negotiate a price, and may go out with him if we have time after the Arctic trip. After dinner Gordon shows some of his underwater video of bells, historic submarines, etc.

3 August 0800 – Packed the vans with diving gear, food, sleeping bags, clothes, and cameras, and set off in the pouring rain. Over the course of the day the weather slowly improved, dry by afternoon. Reached Arctic Circle at 1630, and stopped for coffee, souvenirs, etc. Impressive scenery all day. Took short detour into Sweden for the hell of it. Arrived at overnight accommodation stop 2000, after driving just over 600km. Showers, then began excellent party lasting until small hours. It never really went dark.

4 August Drove north to nearest convenient roadside dive site. It turned out to be a very good dive. I had expected that someone might have buoyancy problems because half of us were using completely unfamiliar equipment, that didn’t fit very well. But the one who did a buoyant ascent – fortunately at the start of the dive and without ill effects – was using her own equipment! An elderly Norwegian couple appeared in a small boat whilst we were diving and started to fish over one set of bubbles. They had no English and we had no Norwegian, but after much gesticulating and shouting from us they moved on, only to motor over to the next set of bubbles and start fishing them instead. After further gesticulating and shouting they abandoned these bubbles, and proceeded to troll their line around the dive site. Eventually they moved off, no doubt bewildered by the hostility and strange dress of English tourists. It was like a scene from Beadle’s About.

After a harrowing visit to a local museum dedicated to slave labour in the last war, we drove south to Mo-i-Rana for a picnic tea. Afterwards we split into two parties. Six, including engineers Steve, John and Gordon, would return to be ready to start work on the gearbox as soon as the parts arrive. On return JU cooks soup which needs a knife & fork to eat.

The rest would stay an extra night and visit the Svartisen glacier the next day, Monday. It didn’t take long to find comfortable accommodation complete with bath and dishwasher. A trip to a nearby supermarket provided the ingredients for a Norwegian style evening meal including Rudolphburgers and sweet brown cheese.

5 August The trip to the glacier provided further adventure. The signposted road to Svartisen was impassable due to roadworks which involved a trench right across the road. A workman gave us a hand drawn map of an alternative route. This took some following, because the correct road was signposted as a no through road. Eventually we found the right route, but after a few miles that too was blocked by roadworks – the road was actually being rebuilt and was completely impassable. However after a few minutes one of the workmen climbed into a bulldozer and bulldozed a path through especially for us. The glacier terminates in an iceberg filled lake. On seeing the pictures of the lake in a guidebook the previous evening we had considered diving it. However on closer investigation it turned out that this was the upper of two lakes. The lower lake is accessible by road, but presented no special diving challenge. It is like an icy cold lakeland tarn with extremely poor vis due to the glacier debris it contains. The upper lake is dangerous because of the waves up to 5 metres formed when pieces of glacier break off, and the drainage tunnel which has been built to lower its level. Water comes from the foot of this tunnel with incredible force. It would make the ultimate, suicidal, drift dive. Diving the upper lake would also require carrying equipment by boat across the lower lake and on foot 3km to the upper lake. Although tempted, I decided reluctantly that this was not a proposition for an impromptu dive, when our tanks were less than half full, we already had only one set of gear between two, and we had no suitable rucksacks to carry anything in.

The glacier was magnificent.

2200 – Arrived back at Rørvik. Bearings still not arrived. Dives had been made in the sound outside the harbour and in the harbour itself. Fish for tea tomorrow!

6 August 0800 – ETA for bearings now Friday. So much for DHL 24 hour claims. Enquiries reveal that if we pay extra, bearings can be flown to Trondheim. Reluctantly take this option and Steve B sets off by car to collect. 1000 – Ring Sievert to arrange wreck dive. Dive will require transport by road and boat. Boat only takes 6 so we will need two waves.

1400 – Set off for dive. Wreck turns out to one of the most intact I have ever dived – excellent. Lovely weather. Boat launches from spectacularly rickety pier reached through shed full of dried fish. Wheelbarrow supplied for gear transport.

2000 – Hero Steve returns with bearings, and engineers commence rebuilding of gearbox.

2300 – On my visit to the yacht club for a last shower before putting to sea I discover that on the wall is the local chart annotated with the name and exact location of a dozen wrecks! I make hasty notes while the concierge waits to lock up.

7 August 0200 – Sail south from Rørvik. Gearbox still running hot. Believed to be due to alignment problem. Reduce revs and set course towards nearest harbour for adjustments. 0700 – Tie up alongside jetty made of boulder and concrete filled wreck. Engineers correct alignment, and we fill water tanks and barrels from a very peaty supply. Sail south again at full speed.

1400 – Excellent dive with ocean feel off isolated lighthouse.

Continue sailing overnight. Weather calm so take outside route as much as possible.

8 August 1000 – Original dive site choice was scenic dive on island. However it’s so calm I decide we should dive an isolated rock where the swell is just breaking – it’s the sort of place you might find a wreck. Gordon will be first in and I will drive the boat. As the divers kit up, a local dive boat arrives and anchors nearby – this looks promising. Almost as soon as Gordon has submerged he surfaces again, calling for a waster – we’re on a wreck! It turns out to be the Wavelet a British ore carrier lost in 1916. Definitely one of my best choices of dive site. 1400 – Surprise visit from King Neptune. He has decided that although we didn’t cross the Arctic Circle by sea, our Arctic dive qualifies us for Arctic Bluenose certificates. A short ceremony ensues. This is a naval tradition researched by Steve Maloney (see Appendix C).

Later the traditional Maisie Graham Furthest North Time Capsule is released overboard.

2000 – Second dive is on the big wreck at Alesund. As usual we anchor in with a grapnel which the first pair in release, replacing it with a waster. On this occasion the tender of the waster is a “green nugget” in these matters who mistakes the pull from a gentle tide for the pull of the diver. Consequently, 200 metres of line are released before the waster is made fast on the boat. On surfacing, the first pair are less than complimentary following their unexpectedly long swim back to the boat.

2130 – Put into Ålesund and spend an agreeable night ashore.

9 August 0445 – Sail south again. 0900 – Once again calm rounding Statlandet, once again no time to stop and explore.

1330 – Look for the wreck passed over on the outward trip. Find it and confirm it’s too deep (and also right in the middle of the busy and narrow shipping channel). While looking for two shallower wrecks nearby, boat from local dive centre comes out to see us. They had seen us on the way north. They tell us the wrecks we are looking for aren’t worth diving. They show us the position of another nearby, but we’ve missed slack. They tell us the names of some of the other charted wrecks we’ve marked. One of them is buoyed. They are just off to look for some wrecks they know of but haven’t found yet…

1500 – We dive a magnificent wall which drops vertically from 20 to 160 metres.

1600 – Tie up at an old jetty and go ashore to explore old coastal fortifications. These are extensive. There are two big guns up on the hill, one of them Russian and dated 1940, and lots of bunkers built into the mountainside. The area under the jetty would make a wonderful rummaging dive, and just beyond it is another big wall. But we have to press on.

2000 – Weather has deteriorated – squally showers – but holds off while we make a detour for a wreck dive. It’s buoyed, and called Helga Ferdinand – upright and very intact, but 45m to the deck. RJW is first in with the waster – it was he who got 200m of line at Ålesund. Jen tends the line this time to make sure there are no mistakes. After the agreed time I tell Jen to winch the line tight and make it off. She says she hasn’t had the signal yet. I say do it anyway, he’s had long enough. Unfortunately he hasn’t. The good news is that he’s a big strong lad.

2130 – Roz complains of a sore face, tightness in the chest and feeling weak 1 hour after the dive. I don’t think it’s DCI – she’s been stung by a jellyfish and also not had much sleep. We give her Piriton, and some oxygen to be on the safe side. She’s OK later.

2300 – Arrived Florø.

10 August 0900 – set off to dive a wreck we’d been told about with 3000 bottles of wine on it. It was said to be buoyed. We investigated several buoys and did a sounder search of the area but didn’t find anything. Ran out of time so dived a wreck which showed instead. One member, a keen rummager was taking too long and had to be persuaded to the surface with a thunderflash. 1100 – Set sail for Bergen.

1355 – UK Shipping Forecast for homeward passage less than encouraging – North Utsire SE 5-7 occasionally 8. This could delay Maisie Graham’s return beyond Wednesday night.

We pass various tempting wall dives, and some charted wrecks. But eta Bergen is already 2300 so we pass them by.

1750 – No change in forecast

2000 – Pat removes splinter from Gordon’s nether regions. Patient writhing around to avoid cameras.

2300 – Arrive Bergen. Drinks on board then out on the town. Nigel disembarks to stay with friends in Bergen.

11 August 0045 – Unable to receive forecast. 0550 – Sleep through this forecast

0900 – Up for breakfast then sightseeing trip on funicular. I have to be back at work on Thursday morning to sort out a crucial project which had been just about to start when I left. In absence of better forecast I decide to return by ferry, since options like stopping a night in Stavanger or returning via Shetland would delay return. (In the event Maisie Graham gets back early, and when I arrive at work I discover the critical project has been postponed)

1430 – Nine crew disembark to catch ferry. Maisie Graham leaves for UK.

1630 – Ferry sails

1750 – Better forecast, weather moderated to SE5. Maisie Graham sets course directly from Bergen towards Scarborough.

2000 – Celebration dinner on ferry.

2330 – JU accosted by dancing girls during cabaret on ferry – this matter now sub judice!

12 August Ferry arrives 1600, after smooth crossing. Pick up vehicles and disperse.

Maisie Graham still on passage.13 August Maisie Graham still on passage. 14 August 0230 – Maisie Graham arrives Scarborough, having made best possible time. 1500 – Ferry party arrive to collect gear, and copies of video.

9. Appendix B – Expedition Publicity

Maisie Graham Adventures

Private Expedition to Arctic Norway

2 or 3 weeks – late July/early August 1996

We are looking for suitable members for a self-contained diving expedition to reach inside the Arctic Circle next summer. The expedition is still in the planning stages and will adapt to the wishes of its members. The following is an outline:

- The boat is Maisie Graham, a 54 foot converted MFV based in Scarborough, owned and

skippered by Gordon Wadsworth. She has an outstanding track record for expedition diving over the last decade, including Norway 1995, St Kilda 1994, and scores of high-yield virgin wrecks. She is extremely well equipped for diving expeditions. There are video recording and playback facilities on board, and a production quality video of the trip is to be made.

- Maisie Graham will depart Scarborough (54°10´N 0°15´E) about Thursday 24th July and

return about Tuesday 13th August, depending on the weather. - The expedition will be in Norwegian waters for 2 weeks. Those who are unable to manage the full 3 week trip including the North Sea crossings, will be picked up in Bergen (60°14´N 5°4´E) after crossing from Newcastle by ferry.. The return ferry trip costs between £115 and £136 depending on how many persons book together. Diving gear can be transported on board Maisie Graham if required. The ferries are operated by Color Line and the times are:Depart Newcastle Saturday 27th July 1330, arriving Bergen 1400 Sunday

Depart Bergen Sunday 11th August 1600 arriving Newcastle 1430 Monday 12th August. - In Norway, to comply with Norwegian regulations, we will be accompanied by a local diver who will act as our interpreter.

- After the pickup in Bergen, we will head north for the Arctic Circle (66°32´N) as quickly as possible, in the shelter of the many offshore islands, stopping to dive twice a day. Depending on the weather and our inclination, we may get as far as the Lofoten Islands (67°30´N) or even Narvik (68°15´N 17°15´E). We shall then work our way south visiting previously found wrecks and scenic sites from the 1995 expedition, and searching for new sites en route.

- We will be doing further research on potential wreck and other sites between now and next summer. There were German naval bases at Narvik, Bodø, Trondheim, and Bergen during the last war, and there are records of naval actions around each of these places. In April 1940 there was extensive fighting around Narvik when ten German and two British destroyers were sunk. Help with research would be appreciated.

- The diving will not be looking to push the limits, but to get the most out of the trip members should be completely competent. Ideally, expedition members should be experienced divers capable of acting as a reliable buddy on rectangular profile dives to 50 metres with stage decompression in offshore conditions. However, there is currently no plan to undertake a large number of very deep dives.

- This is a self-contained, hands-on expedition. Members will be expected to play a full part in cooking, cleaning, bottle filling, navigation, helming (including night sailing) etc as necessary and in line with their skills.

- The cost of the expedition will be based on shared expenses. The likely cost is about £600

whether you go for 2 or 3 weeks (the boat still has to be paid for from leaving the UK). £200 deposit required by end of January 1996, plus ferry booking if required.For more details contact :

Richard Scarsbrook

35A Rossett Avenue, Timperley, WA15 6EU

scarsbrook@supanet.com

or Gordon Wadsworth

01723 362085 8 Ryndle Walk, Scarborough, YO12 6JU10. Appendix C – Arctic Bluenose Ceremony

This is a Naval tradition, researched by Steve Maloney. King Neptune awards certificates to those crossing the Arctic Circle for the first time. The certificate text reads as follows ;-

We, Neptunus Arcticus, Rex, Sovereign of the seas,

ruler of the deep, by these patents;

Admit {name} of {vessel} into the Northern Realm of Our Domain.

Having braved the elements of Our Arctic Kingdom and the perils of the icy

depths we adjudge {him/her}, a true ‘Bluenose’.

All icebergs, whales, dolphins, landlubbers and mariners of the temperate climes

are to show {him/her} due deference under penalty of Our Imperial displeasure.

Given under Our Grand Seal this {day} day of {month} {year in words}

in Longitude {long}